Real Life Examples of Entropy Real Life Examples of Continuity Equation

6.7 Examples of Lost Work in Engineering Processes

- Lost work in Adiabatic Throttling: Entropy and Stagnation Pressure Changes

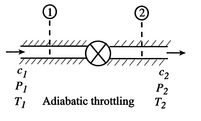

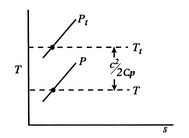

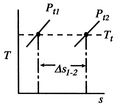

Figure 6.8: Adiabatic Throttling

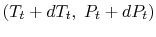

A process we have encountered before is adiabatic throttling of a gas, by a valve or other device as shown in Figure 6.8. The velocity is denoted by

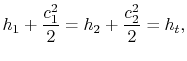

. There is no shaft work and no heat transfer and the flow is steady. Under these conditions we can use the first law for a control volume (the Steady Flow Energy Equation) to make a statement about the conditions upstream and downstream of the valve:

. There is no shaft work and no heat transfer and the flow is steady. Under these conditions we can use the first law for a control volume (the Steady Flow Energy Equation) to make a statement about the conditions upstream and downstream of the valve:

where

is the stagnation enthalpy, corresponding to a (possibly fictitious) state with zero velocity. The stagnation enthalpy is the same at stations 1 and 2 if

is the stagnation enthalpy, corresponding to a (possibly fictitious) state with zero velocity. The stagnation enthalpy is the same at stations 1 and 2 if  , even if the flow processes are not reversible.

, even if the flow processes are not reversible. For a perfect gas with constant specific heats,

and

and  . The relation between the static and stagnation temperatures is:

. The relation between the static and stagnation temperatures is:

where is the speed of sound and

is the speed of sound and  is the Mach number,

is the Mach number,  . In deriving this result, use has only been made of the first law, the equation of state, the speed of sound, and the definition of the Mach number. Nothing has yet been specified about whether the process of stagnating the fluid is reversible or irreversible.

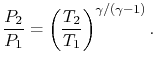

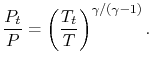

. In deriving this result, use has only been made of the first law, the equation of state, the speed of sound, and the definition of the Mach number. Nothing has yet been specified about whether the process of stagnating the fluid is reversible or irreversible. When we define the stagnation pressure, however, we do it with respect to isentropic deceleration to the zero velocity state. For an isentropic process

The relation between static and stagnation pressures is

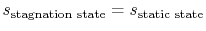

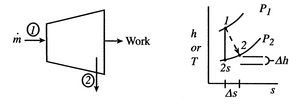

Figure 6.9: Static and stagnation pressures and temperatures

The stagnation state is defined by

,

,  . In addition,

. In addition,  . The static and stagnation states are shown in

. The static and stagnation states are shown in  -

-  coordinates in Figure 6.9.

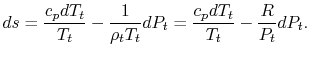

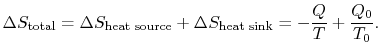

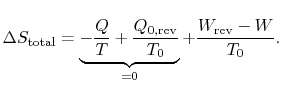

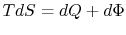

coordinates in Figure 6.9. Stagnation pressure is a key variable in propulsion and power systems. To see why, we examine the relation between stagnation pressure, stagnation temperature, and entropy. The form of the combined first and second law that uses enthalpy is

(6..8)

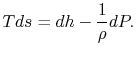

Figure 6.10: Stagnation and static states

This holds for small changes between any thermodynamic states and we can apply it to a situation in which we consider differences between stagnation states, say one state having properties

and the other having properties

and the other having properties  (see Figure 6.10). The corresponding static states are also indicated. Because the entropy is the same at static and stagnation conditions,

(see Figure 6.10). The corresponding static states are also indicated. Because the entropy is the same at static and stagnation conditions,  needs no subscript. Writing (6.8) in terms of stagnation conditions yields

needs no subscript. Writing (6.8) in terms of stagnation conditions yields

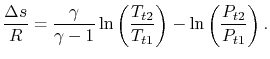

Both sides of the above are perfect differentials and can be integrated as

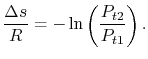

For a process with

, the stagnation enthalpy, and hence the stagnation temperature, is constant. In this situation, the stagnation pressure is related directly to the entropy as,

, the stagnation enthalpy, and hence the stagnation temperature, is constant. In this situation, the stagnation pressure is related directly to the entropy as,

(6..9)

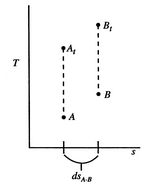

Figure 6.11: Losses reflected in changes in stagnation pressure when

Figure 6.11 shows this relation on a

-

-  diagram. We have seen that the entropy is related to the loss, or irreversibility. The stagnation pressure plays the role of an indicator of loss if the stagnation temperature is constant. The utility is that it is the stagnation pressure (and temperature) which are directly measured, not the entropy. The throttling process is a representation of flow through inlets, nozzles, stationary turbomachinery blades, and the use of stagnation pressure as a measure of loss is a practice that has widespread application.

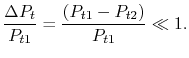

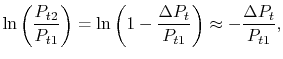

diagram. We have seen that the entropy is related to the loss, or irreversibility. The stagnation pressure plays the role of an indicator of loss if the stagnation temperature is constant. The utility is that it is the stagnation pressure (and temperature) which are directly measured, not the entropy. The throttling process is a representation of flow through inlets, nozzles, stationary turbomachinery blades, and the use of stagnation pressure as a measure of loss is a practice that has widespread application. Equation (6.9) can be put in several useful approximate forms. First, we note that for aerospace applications we are (hopefully!) concerned with low loss devices, so that the stagnation pressure change is small compared to the inlet level of stagnation pressure,

Expanding the logarithm (using

),

),

or

Another useful form is obtained by dividing both sides by

and taking the limiting forms of the expression for stagnation pressure in the limit of low Mach number (

and taking the limiting forms of the expression for stagnation pressure in the limit of low Mach number (  ). Doing this, we find:

). Doing this, we find:

The quantity on the right can be interpreted as the change in the ``Bernoulli constant'' for incompressible (low Mach number) flow. The quantity on the left is a non-dimensional entropy change parameter, with the term

now representing the loss of mechanical energy associated with the change in stagnation pressure.

now representing the loss of mechanical energy associated with the change in stagnation pressure. To summarize:

- For many applications the stagnation temperature is constant and the change in stagnation pressure is a direct measure of the entropy increase.

- Stagnation pressure is the quantity that is actually measured so that linking it to entropy (which is not measured) is useful.

- We can regard the throttling process as a ``free expansion'' at constant temperature

from the initial stagnation pressure to the final stagnation pressure. We thus know that, for the process, the work we need to do to bring the gas back to the initial state is

from the initial stagnation pressure to the final stagnation pressure. We thus know that, for the process, the work we need to do to bring the gas back to the initial state is  , which is the ``lost work'' per unit mass.

, which is the ``lost work'' per unit mass.

Muddy Points

Why do we find stagnation enthalpy if the velocity never equals zero in the flow? (MP 6.13)

Why does

remain constant for throttling? (MP 6.14)

remain constant for throttling? (MP 6.14) - Adiabatic Efficiency of a Propulsion System Component (Turbine)

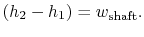

Figure 6.12: Schematic of turbine and associated thermodynamic representation in  -

-  coordinates

coordinates

A schematic of a turbine and the accompanying thermodynamic diagram are given in Figure 6.12. There is a pressure and temperature drop through the turbine and it produces work. There is no heat transfer so the expressions that describe the overall shaft work and the shaft work per unit mass are

If the difference in the kinetic energy at inlet and outlet can be neglected, Equation (6.11) reduces to

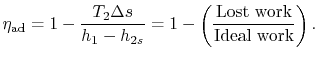

The adiabatic efficiency of the turbine is defined as

The performance of the turbine can be represented in an![$\displaystyle \eta_\textrm{ad} = \left[\frac{\textrm{actual work}} {\textrm{ideal work $(\Delta s=0)$}}\right]_\textrm{for a given pressure ratio}.$](https://web.mit.edu/16.unified/www/FALL/thermodynamics/notes/img799.png)

-

-  plane (similar to a

plane (similar to a  -

-  plane for a perfect gas with constant specific heats) as shown in Figure 6.12. From the figure the adiabatic efficiency is

plane for a perfect gas with constant specific heats) as shown in Figure 6.12. From the figure the adiabatic efficiency is

The adiabatic efficiency can therefore be written as

The non-dimensional term

represents the departure from isentropic (reversible) processes and hence a loss. The quantity

represents the departure from isentropic (reversible) processes and hence a loss. The quantity  is the enthalpy difference for two states along a constant pressure line (see diagram). From the combined first and second laws, for a constant pressure process, small changes in enthalpy are related to the entropy change by

is the enthalpy difference for two states along a constant pressure line (see diagram). From the combined first and second laws, for a constant pressure process, small changes in enthalpy are related to the entropy change by  , or approximately,

, or approximately,

The adiabatic efficiency can thus be approximated as

The quantity

represents a useful figure of merit for fluid machinery inefficiency due to irreversibility.

represents a useful figure of merit for fluid machinery inefficiency due to irreversibility. Muddy Points

How do you tell the difference between shaft work/power and flow work in a turbine, both conceptually and mathematically? (MP 6.15)

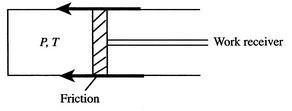

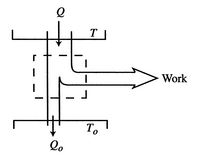

- Isothermal Expansion with Friction

Figure 6.13: Isothermal expansion with friction

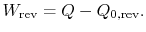

In a more general look at the isothermal expansion, we now drop the restriction to frictionless processes. As seen in Figure 6.13, work is done to overcome friction. If the kinetic energy of the piston is negligible, a balance of forces tells us that

During the expansion, the piston and the walls of the container will heat up because of the friction. The heat will be (eventually) transferred to the atmosphere; all frictional work ends up as heat transferred to the surrounding atmosphere.

The amount of heat transferred to the atmosphere due to the frictional work only is thus,

The entropy change of the atmosphere (considered as a heat reservoir) due to the frictional work is

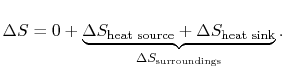

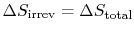

The engine operates in a cycle and the entropy change for the complete cycle is zero (because entropy is a state variable). Therefore,

The total entropy change is

Suppose we had an ideal reversible engine working between these same two temperatures, which extracted the same amount of heat,

, from the high temperature reservoir, and rejected heat of magnitude

, from the high temperature reservoir, and rejected heat of magnitude  to the low temperature reservoir. The work done by this reversible engine is

to the low temperature reservoir. The work done by this reversible engine is

For the reversible engine the total entropy change over a cycle is

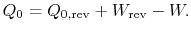

Combining the expressions for work and for the entropy changes,

The entropy change for the irreversible cycle can therefore be written as

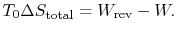

The difference in work that the two cycles produce is proportional to the entropy that is generated during the cycle:

The second law states that the total entropy generated is greater than zero for an irreversible process, so that the reversible work is greater than the actual work of the irreversible cycle.

An ``engine effectiveness,''

, can be defined as the ratio of the actual work obtained divided by the work that would have been delivered by a reversible engine operating between the two temperatures

, can be defined as the ratio of the actual work obtained divided by the work that would have been delivered by a reversible engine operating between the two temperatures  and

and  :

:

The departure from a reversible process is directly reflected in the entropy change and the decrease in engine effectiveness.Muddy Points

Why does

? (MP 6.17)

? (MP 6.17) In discussing the terms ``closed system'' and ``isolated system,'' can you assume that you are discussing a cycle or not? (MP 6.18)

Does a cycle process have to have

? (MP 6.19)

? (MP 6.19) In a real heat engine, with friction and losses, why is

still 0 if

still 0 if  ? (MP 6.20)

? (MP 6.20) - Propulsive Power and Entropy Flux

The final example in this section combines a number of ideas presented in this subject and in Unified in the development of a relation between entropy generation and power needed to propel a vehicle.

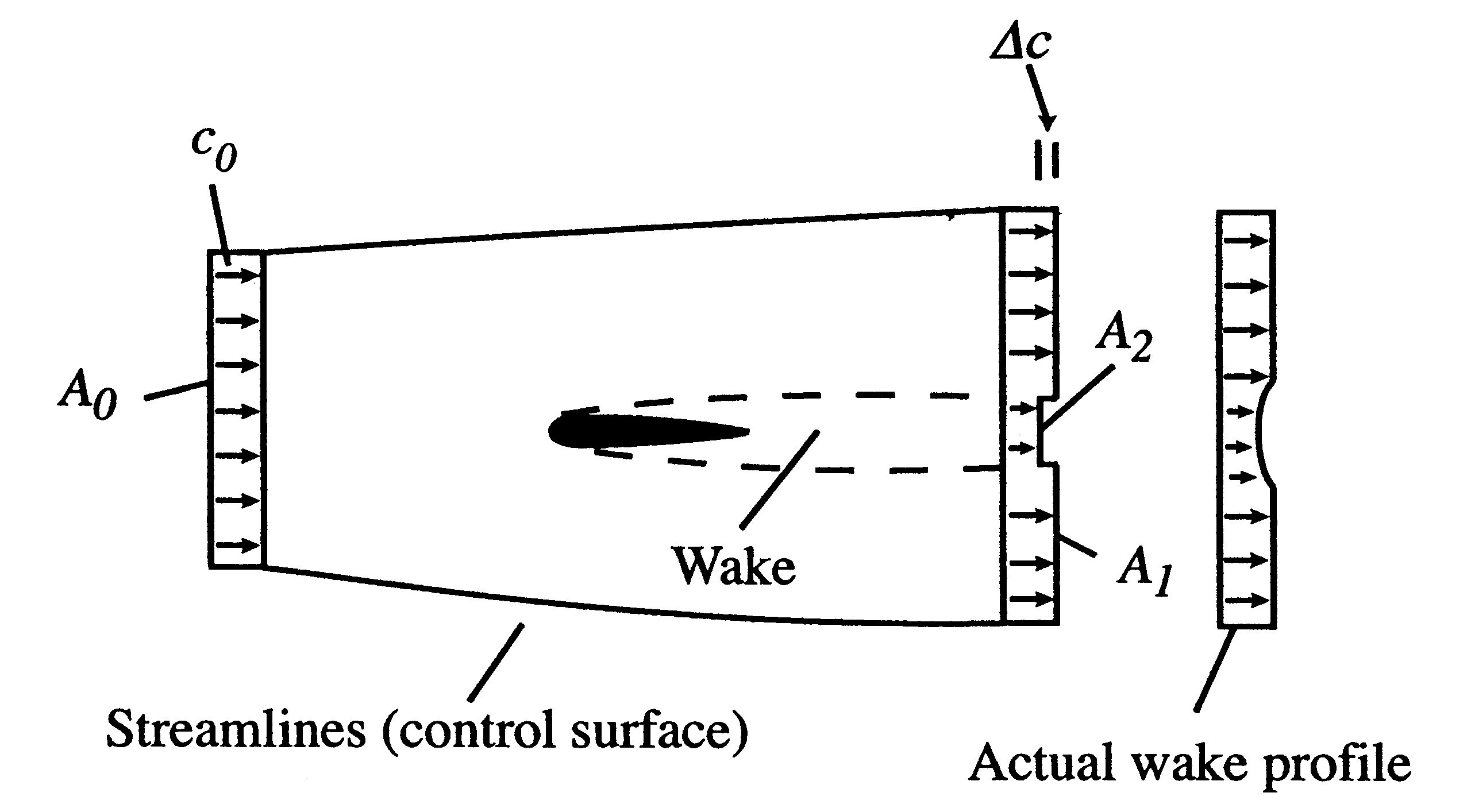

Figure 6.15 shows an aerodynamic shape (airfoil) moving through the atmosphere at a constant velocity. A coordinate system fixed to the vehicle has been adopted so that we see the airfoil as fixed and the air far away from the airfoil moving at a velocity

. Streamlines of the flow have been sketched, as has the velocity distribution at station ``0'' far upstream and station ``d'' far downstream.

. Streamlines of the flow have been sketched, as has the velocity distribution at station ``0'' far upstream and station ``d'' far downstream. The airfoil has a wake, which mixes with the surrounding air and grows in the downstream direction. The extent of the wake is also indicated. Because of the lower velocity in the wake the area between the stream surfaces is larger downstream than upstream.

Figure 6.15: Airfoil with wake and control volume for analysis of propulsive power requirement

We use a control volume description and take the control surface to be defined by the two stream surfaces and two planes at station 0 and station d. This is useful in simplifying the analysis because there is no flow across the stream surfaces. The area of the downstream plane control surface is broken into

, which is the area outside the wake and

, which is the area outside the wake and  , which is the area occupied by wake fluid, i.e., fluid that has suffered viscous losses. The control surface is also taken far enough away from the vehicle so that the static pressure can be considered uniform. For fluid which is not in the wake (no viscous forces), the momentum equation is

, which is the area occupied by wake fluid, i.e., fluid that has suffered viscous losses. The control surface is also taken far enough away from the vehicle so that the static pressure can be considered uniform. For fluid which is not in the wake (no viscous forces), the momentum equation is

Uniform static pressure therefore implies uniform velocity, so that on

the velocity is equal to the upstream value,

the velocity is equal to the upstream value,  . The downstream velocity profile is actually continuous, as indicated. It is approximated in the analysis as a step change to make the algebra a bit simpler. (The conclusions apply to the more general velocity profile as well and we would just need to use integrals over the wake instead of the algebraic expressions below.)

. The downstream velocity profile is actually continuous, as indicated. It is approximated in the analysis as a step change to make the algebra a bit simpler. (The conclusions apply to the more general velocity profile as well and we would just need to use integrals over the wake instead of the algebraic expressions below.) The equation expressing mass conservation for the control volume is

(6..12)

The vertical face of the control surface is far downstream of the body. By this station, the wake fluid has had much time to mix and the velocity in the wake is close to the free stream value, . We can thus write,

. We can thus write,

(6..13)

(We chose our control surface so the condition was upheld.)

was upheld.) The integral momentum equation (control volume form of the momentum equation) can be used to find the drag on the vehicle:

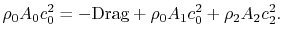

(6..14) There is no pressure contribution in Eq. (6.14) because the static pressure on the control surface is uniform. Using the form given for the wake velocity and expanding the terms in the momentum equation we obtain

![$\displaystyle \rho_0 A_0 c_0^2 = -\textrm{Drag} +\rho_0 A_1 c_0^2 +\rho_2 A_2[c_0^2 - 2c_0\Delta c + (\Delta c)^2].$](https://web.mit.edu/16.unified/www/FALL/thermodynamics/notes/img834.png)

(6..15)

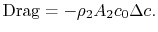

The last term in the right hand side of the momentum equation, , is small by virtue of the choice of control surface and we can neglect it. Doing this and grouping the terms on the right hand side of Eq. (6.15) in a different manner, we have

, is small by virtue of the choice of control surface and we can neglect it. Doing this and grouping the terms on the right hand side of Eq. (6.15) in a different manner, we have

The terms in the square brackets on both sides of this equation are the continuity equation multiplied by![$\displaystyle c_0[\rho_0 A_0 c_0] = c_0[\rho_0 A_1 c_0 +\rho_2 A_2 (c_0-\Delta c)] +\{-\textrm{Drag} -\rho_2 A_2 c_0 \Delta c\}.$](https://web.mit.edu/16.unified/www/FALL/thermodynamics/notes/img836.png)

. They thus sum to zero leaving the curly bracketed terms as

. They thus sum to zero leaving the curly bracketed terms as

(6..16)

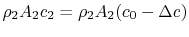

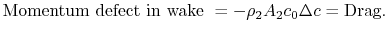

The wake mass flow is . All this flow has a velocity defect (compared to the free stream) of

. All this flow has a velocity defect (compared to the free stream) of  , so that the defect in flux of momentum (the mass flow in the wake times the velocity defect) is, to first order in

, so that the defect in flux of momentum (the mass flow in the wake times the velocity defect) is, to first order in  ,

,

The combined first and second law gives us a means of relating the entropy and velocity:

The pressure is uniform (

) at the downstream station. There is no net shaft work or heat transfer to the wake so that the mass flux of stagnation enthalpy is constant. We can also approximate that the condition of constant stagnation enthalpy holds locally on all streamlines. Applying both of these to the combined first and second law yields

) at the downstream station. There is no net shaft work or heat transfer to the wake so that the mass flux of stagnation enthalpy is constant. We can also approximate that the condition of constant stagnation enthalpy holds locally on all streamlines. Applying both of these to the combined first and second law yields

For the present situation,

;

;  , so that

, so that

(6..17)

In Equation (6.17) the upstream temperature is used because differences between wake quantities and upstream quantities are small at the downstream control station. The entropy can be related to the drag as

(6..18)

The quantity is the entropy flux (mass flux times the entropy increase per unit mass; in the general case we would express this by an integral over the locally varying wake velocity and density). The power needed to propel the vehicle is the product of

is the entropy flux (mass flux times the entropy increase per unit mass; in the general case we would express this by an integral over the locally varying wake velocity and density). The power needed to propel the vehicle is the product of  ,

,  . From Eq. (6.18), this can be related to the entropy flux in the wake to yield a compact expression for the propulsive power needed in terms of the wake entropy flux:

. From Eq. (6.18), this can be related to the entropy flux in the wake to yield a compact expression for the propulsive power needed in terms of the wake entropy flux:

(6..19)

This amount of work is dissipated per unit time in connection with sustaining the vehicle motion. Equation (6.19) is another demonstration of the relation between lost work and entropy generation, in this case manifested as power that needs to be supplied because of dissipation in the wake.

Muddy Points

Is it safe to say that entropy is the tendency for a system to go into disorder? (MP 6.21)

UnifiedTPSource: https://web.mit.edu/16.unified/www/FALL/thermodynamics/notes/node50.html

Post a Comment for "Real Life Examples of Entropy Real Life Examples of Continuity Equation"